Larry E. Jones

What's New?

"Is There "Too Much" Inequality in Health Spending Across Income Groups?" with Laurence Ales and Roozbeh Hosseini, March 2012.

In this paper we study the efficient allocation of health resources across individuals. We focus on the relation between health resources and income (taken as a proxy for productivity). In particular we determine the efficient level of the health care social safety net for the indigent. We assume that individuals have different life cycle profiles of productivity. Health care increases survival probability. We adopt the classical approach of welfare economics by considering how a central planner with an egalitarian (ex-ante) perspective would allocate resources. We show that, under the efficient allocation, health care spending increases with labor productivity, but only during the working years. Post retirement, everyone would get the same health care. Quantitatively, we find that the amount of inequality across the income distribution in the data is larger that what would be justified solely on the basis of production efficiency, but not drastically so. As a rough summary, in U.S. data top to bottom spending ratios are about 1.5 for most of the life cycle. Efficiency implies a decline from about 2 (at age 25) to 1 at retirement. We find larger inefficiencies in the lower part of the income distribution and in post retirement ages.

"Optimal Contracting with Dynastic Altruism: Family Size and Per Capita Consumption," with Roozbeh Hosseini and Ali Shourideh, March 2012.

We use a Barro-Becker model of endogenous fertility, in which parents are subject to idiosyncratic shocks that are private information (either to labor productivity or taste for leisure), to study the efficient degree of consumption inequality in the long run. The planner uses the trade off between family size and future consumption and leisure, in addition to the usual variables, to provide incentives for workers to reveal their shocks. We show that in this environment, the optimal dynamic contract no longer features immiseration in consumption. We also discuss the implications of the model on the long run properties of family size in the optimal contract and show that the long run trend in dynasty size can be either positive or negative depending on parameters.

"Risk Sharing, Inequality and Fertility," with Roozbeh Hosseini and Ali Shourideh.

We use an extended Barro-Becker model of endogenous fertility, in which parents are heterogeneous in their labor productivity, to study the efficient degree of consumption inequality in the long run. In our environment a utilitarian planner allows for consumption inequality even when labor productivity is public information. We show that adding private information does not alter this result. We also show that the informationally constrained optimal insurance contract has a resetting property -- whenever a family line experiences the highest shock, the continuation utility of each child is reset to a (high) level that is independent of history. This implies that there is a non-trivial, stationary distribution over continuation utilities and there is no mass at misery. The novelty of our approach is that the no-immiseration result is achieved without requiring that the objectives of the planner and the private agents disagree. Because there is no discrepancy between planner and private agents objectives, the policy implications for implementation of the efficient allocation differ from previous results in the literature. Two examples of these are: 1) estate taxes are positive and 2) there are positive taxes on family size.

"Fertility Theories: Can They Explain the Negative Fertility-Income Relationship?," with Alice Schoonbroodt and Michele Tertilt, prepared for the NBER volume on Demography.

There is overwhelming empirical evidence that fertility is negatively related to income in most countries at most times. Several theories have been proposed in the literature to explain this somewhat puzzling fact. The most common one is based on the opportunity cost of time being higher for individuals with higher earnings. Alternatively, people might differ in their desire to procreate and accordingly some people invest more in children and less in market-specific human capital and thus have lower earnings. We revisit these and other possible explanations. We find that these theories are not as robust as is commonly believed. That is, several special assumptions are needed to generate the negative relationship. Not all assumptions are equally plausible. Such findings will be useful to distinguish alternative theories.

Complements versus Substitutes and Trends in Fertility Choice in Dynastic Models joint with Alice Schoonbroodt, February 2009.

AppendixIn this paper, we consider a variation on the Barro/Becker model of fertilty choice in which, contrary to what is usually assumed, family size and per capita utility are substitutes. We find that in

reasonable, calibrated examples, most of the intuitions from the statistical demography literature about the causes of the Fertility Transition are both qualitatively and quantitatively significant. This is in marked contrast to previous studies.

"Efficiency with Endogenous Population Growth" joint with Mikhail Golosov and Michèle Tertilt. Appendix (forthcoming, Econometrica).

In this paper, we generalize the notion of Pareto-efficiency to make it applicable to environments with endogenous populations. Two different efficiency concepts are proposed, P-efficiency and A-efficiency. The two concepts differ in how they treat people that are not born. We show how these concepts relate to the notion of Pareto efficiency when fertility is exogenous. We then prove versions of the first welfare theorem assuming that decision making is efficient within the dynasty. Finally, we give two sets of sufficient conditions for non-cooperative equilibria of family decision problems to be efficient. These include the Barro and Becker model as a special case.“An Economic History of Fertility in the U.S.: 1826-1960,” with Michele Tertilt, The Handbook of Family Economics , Peter Rupert, Ed., forthcoming.

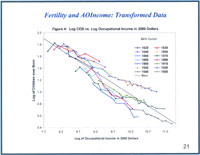

In this paper, we use data from the US census to document the history of the

relationship between fertility choice and key economic indicators at the individual level for women born between 1826 and 1960. We find that this data suggests several new facts that should be useful for researchers trying to model fertility.

- The reduction in fertility known as the Demographic Transition (or the Fertility

Transition) seems to be much sharper based on cohort fertility measures compared to usual measures like Total Fertility Rate;- The baby boom was not quite as large as is suggested by some previous work;

- We find a strong negative relationship between income and fertility for all cohorts and estimate an overall income elasticity of about -0.38 for the period;

- We also find systematic deviations from a time invariant, isoelastic, relationship between income and fertility. The most interesting of these is an increase in the income elasticity of demand for children for the 1876- 1880 to 1906-1910 birth cohorts. This implies an increased spread in fertility by income which was followed by a dramatic compression.

"Baby Busts and Baby Booms: The Fertility Response to Shocks in Dynastic Models," Larry Jones and Alice Schoonbroodt June 2011.

After the fall in fertility during the demographic transition, many developed countries experienced a baby bust, followed by the baby boom and subsequently a return to low fertility (BBB event). Demographers have linked these large fluctuations in fertility to the series of ‘economic shocks' that occurred with similar timing – the Great Depression, World War II (WWII), the economic expansion that followed and then the productivity slow down of the 1970s. This paper is an attempt to formalize a more general link between fluctuations in output and fertility decisions, in simple versions of stochastic growth models with endogenous fertility. First, we develop initial tools to address the effects of ‘temporary' shocks to productivity on fertility choices. These tools are based on a production function, where labor is the only input. Second, we analyze calibrated versions of these models. We can then answer several qualitative and quantitative questions: Is there ‘catching-up' in fertility after a period of particularly low fertility? Under what conditions is fertility pro- or counter-cyclical? How large are these effects? Qualitatively, results show that there is no ‘catching-up' in this model and that under reasonable parameter values fertility is pro-cyclical. Using the U.S. BBB event as a laboratory, we find that the elasticity of fertility to shocks lays between 1 and 2 and, finally, that in these simple models, productivity shocks capture about 70 percent of the pre-WWII baby bust in the U.S.. For the post-WWII baby boom, the predictions of this simple model are small and happen late compared to the data.

The contents of this Web site are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the opinions or policies of the University of Minnesota.