Contact Information

Ellen R. McGrattan

4-161 Hanson Hall

612-625-6714

erm@umn.edu

Office Hours

By appointment

Mailing Address

Department of Economics

University of Minnesota

4-101 Hanson Hall

1925 4th St S

Minneapolis, MN 55455

Previous Work on Intangible-Intensive Businesses

Because firms invest heavily in intangible assets---for example, research and development (R&D), brands, customer bases, and so on---which are typically expensed and only partially counted in gross domestic product (GDP), economic analyses will understate the macroeconomic impacts of business cycle shocks and policy reforms. In work funded by NSF (award 1657891) and the Heller-Hurwicz Economics Institute, McGrattan and coauthors developed theories that explicitly model these intangible investments, taking advantage of newly available macro data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis and micro data from brokered business sales.

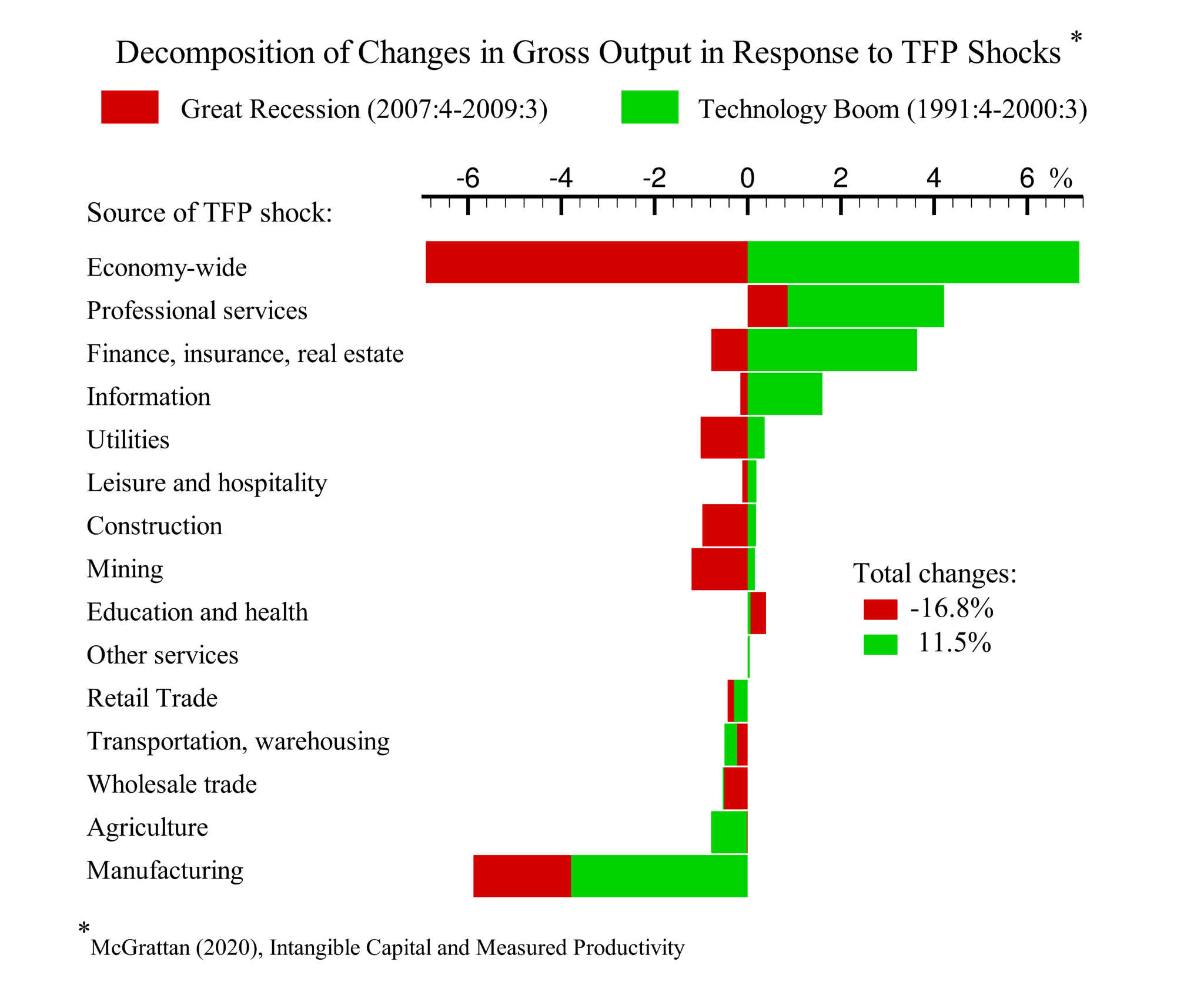

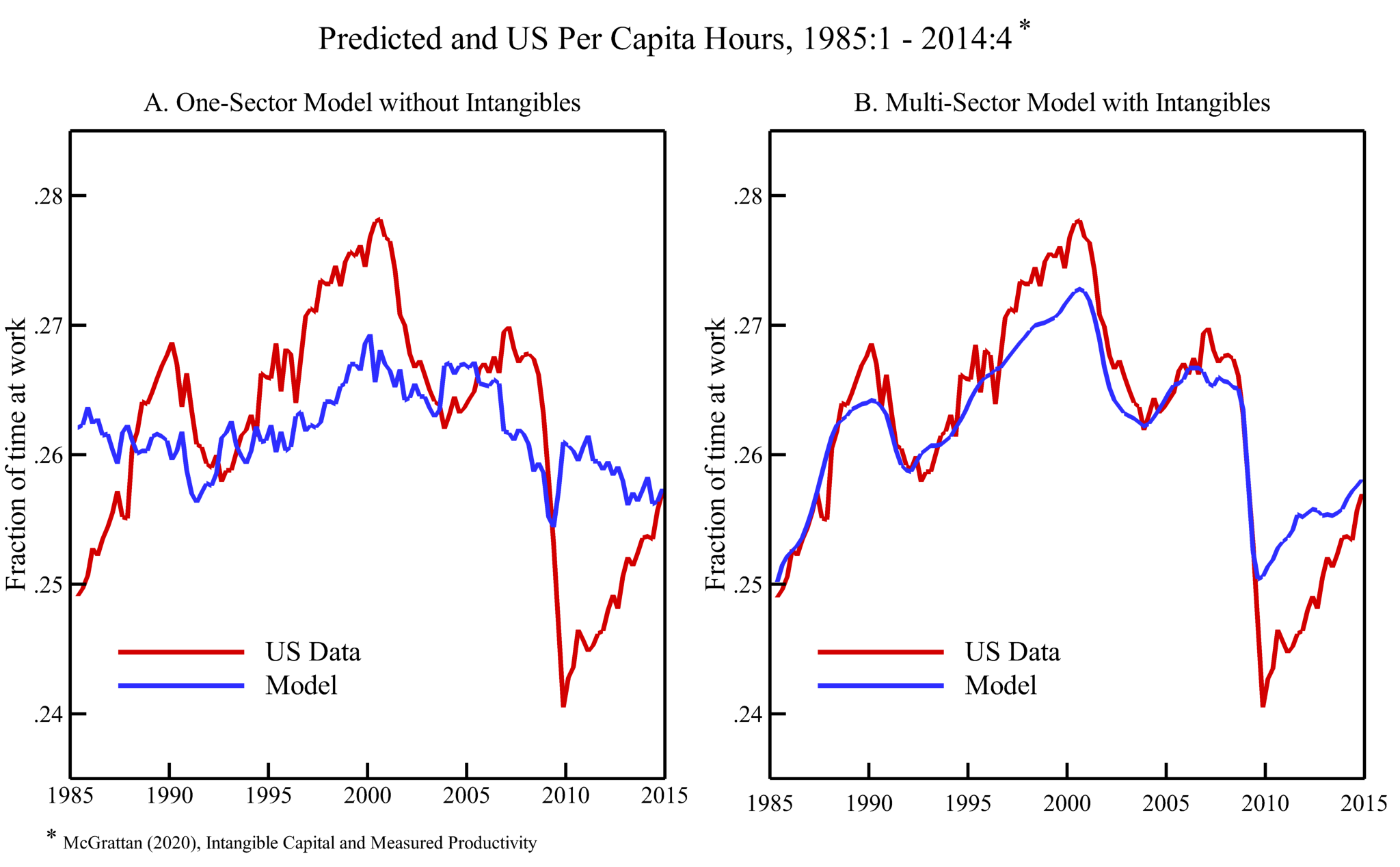

Three applications were studied. The first was a study of the driving forces behind the Great Recession of 2008-2009. The rise in measured productivity at the start of the recession led many economists to reject theories of the business cycle that feature efficient resource allocation and fluctuations driven by shocks to total factor productivities in favor of theories in which financial disruptions have real consequences. With an updated theory and macro dataset, I reassess this view and find that financial shocks had only a small impact on real activity---observed debt levels were relatively high during the period, implying sufficient credit for firms. I find that firm productivity shocks, especially those affecting manufacturing firms, account for much of the decline in gross output during 2008-2009. In the first figure below, I show the contributions of economy-wide and sectoral TFP shocks to changes in US gross output during the Great Recession and the technology boom of the 1990s. In the second figure below, I show that the updated theory incorporating intangible investments does a much better job in accounting for fluctuations in aggregate hours---a prediction that business cycle analysts have struggled with.

space

space

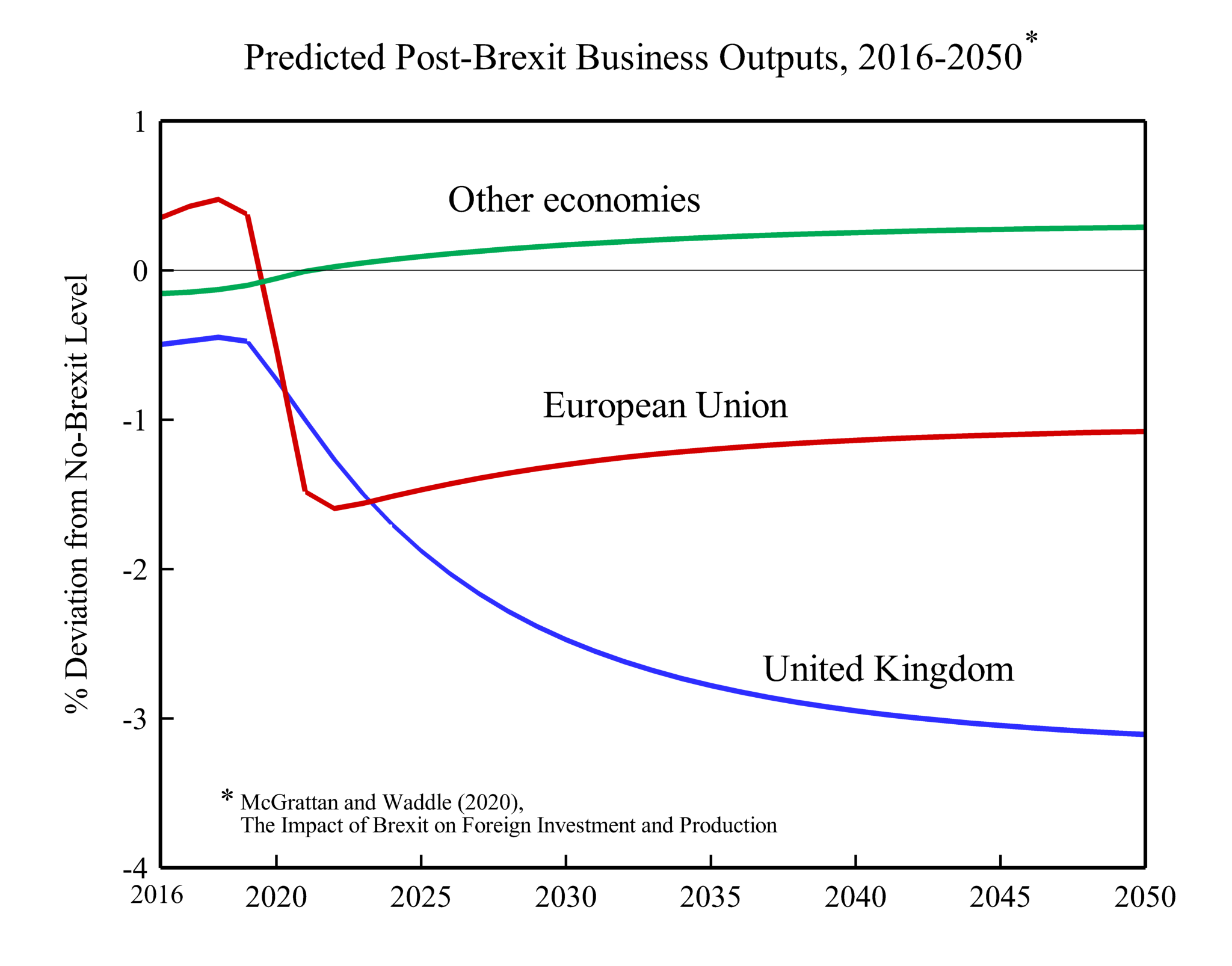

The second application studied the impact of Brexit on foreign investment and production. Critical to this study was the modeling of nonrival intangible capital---for example, patents and brands that can be used simultaneously by a multinational firm producing at home and abroad. Greater restrictions on flows of foreign direct investment between the UK and EU affect the payoffs to R&D and other innovative activity. This, in turn, leads to lower business outputs in both regions (as shown in the third figure below) and lower welfare for UK and EU citizens. Going forward, the theory predicts that the UK would gain overall by entering into trade and investment agreements with nations such as the United States and Japan.

space

space

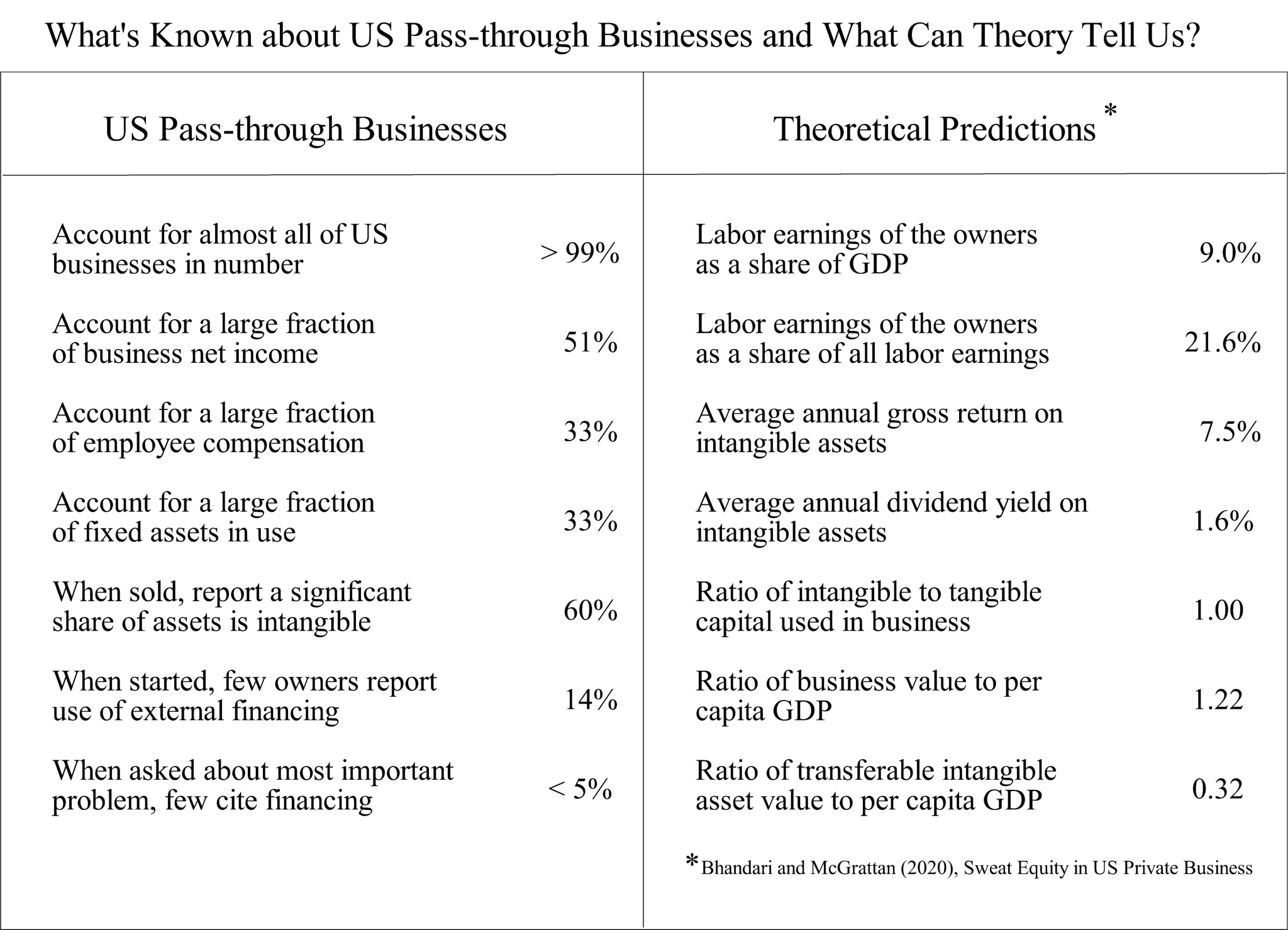

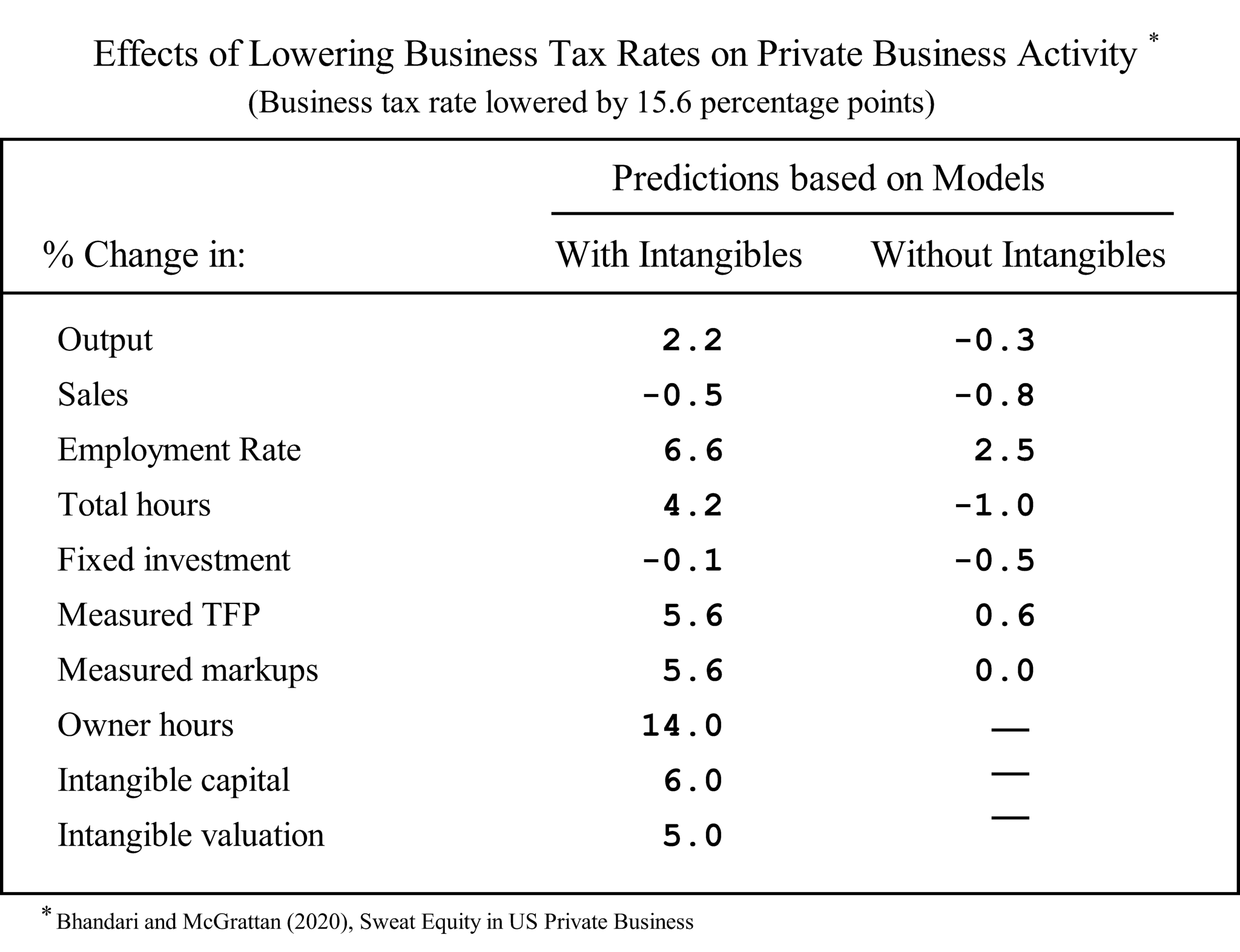

The third application was motivated by observations from business transactions. Specifically, evidence from brokered business sales shows that roughly 60 percent of the value of assets transferred in sales of private firms are classified by the IRS as Section 197 intangibles. Typical examples for private firms are customer bases and tradenames. Because these assets are typically accumulated with time and expenses of business owners (what we call sweat equity), the values are only known at the time of a sale. We developed a theory that can be used to estimate the intangible asset values of ongoing businesses. We parameterized our baseline model using data on pass-through businesses (sole proprietorships, partnerships, and S corporations), which are the primary legal forms of organization for private businesses. In the fourth figure, we report statistics for these businesses in the left panel and inferences we can make with our theory in the right panel. An important take-away is that intangible valuations are about as large as tangible valuations. We also used the model to do policy counterfactuals. Comparing quantitative predictions across models with and without these assets, we found that abstracting from sweat equity leads to a significant understatement of the impacts of lowering business income tax rates on private business activity. The fifth figure shows results for the model with and without owner's sweat investment included.

space

space

space

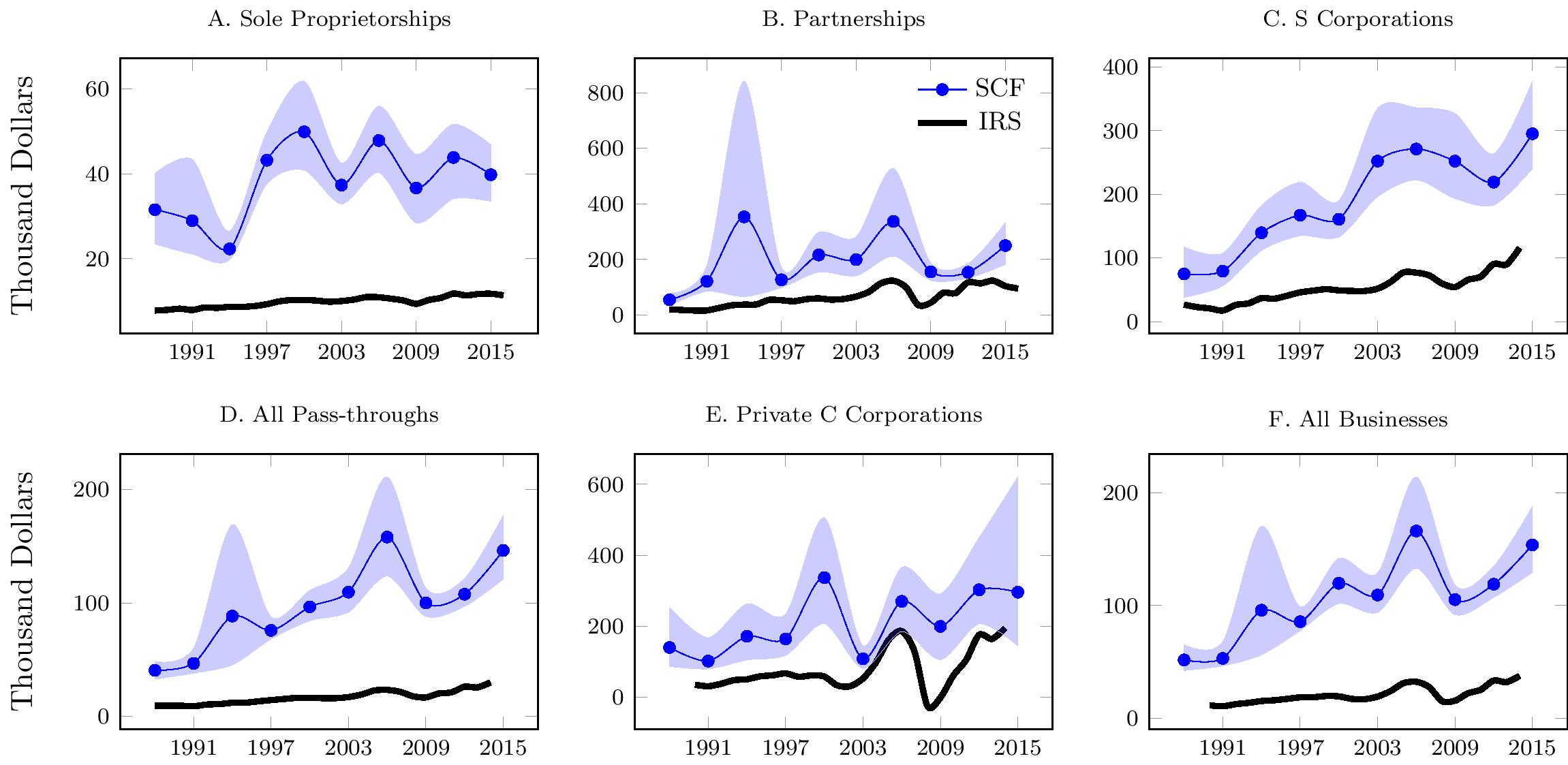

As part of the third application, we also conducted a separate investigation of the accuracy of survey data used in studies of entrepreneurship. A prominent example is the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), which is conducted by the Federal Reserve Board. Business owners are asked to report taxable incomes that appear on specific lines of their IRS business tax forms. We find large and economically relevant discrepancies between the SCF and IRS incomes. For example, in the sixth figure, we show per-return incomes for businesses with different legal forms---these estimates should be exactly the same for the IRS and SCF. In all cases, survey respondents report incomes that are significantly higher than what is actually reported on tax returns. For all businesses (panel F), the error is 434 percent. In the study, we explored reasons for such large discrepancies and proposed corrections for future survey designs.

space

space

space

space

These projects have advanced our knowledge by quantifying the role of intangible investments for business cycle activity and policy reforms. With better access to administrative data, I hope and expect that future research can build on this work with an eye toward informing public policy.

space

space

References: