Econ 1101—Reading 5

International Application

Consumer Goods Manufacturing:

The Rise of

By Thomas J. Holmes, Dept. of

Economics,

Revised October 2014

for Econ 1101

Introduction

In

recent years, in a variety of consumer goods industries, China has emerged as a

manufacturing powerhouse. China already

dominates world markets in certain industries that require relatively

unsophisticated production technologies, like toys and low-end clothing. It also has been “moving up” to include

moderate quality products in its product line.

You can see this for yourself by checking out the Pottery Barn

website and viewing the moderate quality furniture that they sell that is quite

nice, much of it made in

The

rise of China has had a big impact on manufacturing plants making these goods

in the United States. This case study

provides an overview of the impact. Part

1 uses the case study as an opportunity to discuss the theory of exit in

competitive industries, expanding on the numerical example developed in

class. Part 2 presents some statistics

on how particular industries have been affected. Exit has been extremely high but some

industry segments have survived. We

discuss the economics of why some survive and others do not.

Part 1. The Impact of

Low Price Imports on a Competitive Industry

Let’s

use the numerical example from class to illustrate the impact of imports on the

domestic (i.e.,

·

The

same technology is available for all firms.

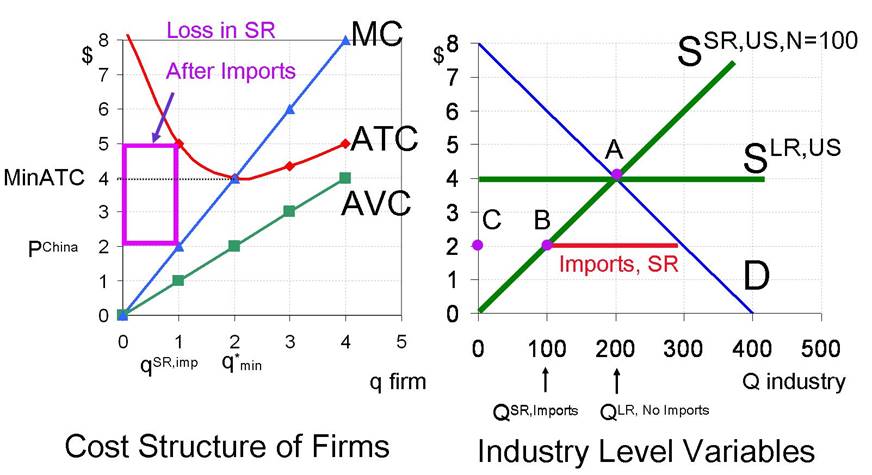

So each domestic firm has the cost structure illustrated in the left

side of Figure 1 below.

·

There

are no barriers to entry.

·

Input

prices to the industry do not go up as the industry expands.

Suppose

that initially there is no possibility of imports from China. This could be because China initially is not

developed enough to be competitive in the particular industry. Or it could be because of trade restrictions

keeping imports out. (There were trade

restrictions on textiles as discussed below.)

Like in class, we can use the information on the firm’s cost structure

(the left side of Figure 1) and the industry-level demand information (right

side of Figure 1) to determine the long-run competitive equilibrium in the

initial situation without imports:

1.

Equilibrium

price equals MinATC = $4 (This is the bottom point of

the U-shaped ATC curve)

2.

Equilibrium

industry quantity equals QLR, No Imports = 200 units. This is domestic demand at price equal to $4

3.

Each

domestic firm sets quantity equal to q*min = 2. This is where MC equals the price of $4. It is also the point where ATC is minimized.

4.

The

number of firms in the industry equals 100 = 200/2. (The 100 firms each produce 2 units so total

supply of 200 equals demand.)

This

takes us to point A in the figure

below.

Figure 1:

Example of the Effect of Imports in the Short Run and the Long Run

|

Variable |

Definition |

|

MC |

Marginal

Cost |

|

ATC |

Average

Total Cost |

|

AVC |

Average

Variable Cost |

|

MinATC |

Minimum of

Average Variable Cost |

|

q*min |

The quantity

where MinATC is attained |

|

SSR,US,N=100 |

The

short-run supply in the initial situation with 100 firms |

|

SLR |

The long-run

domestic supply curve for this industry. |

|

QLR,No Imports |

Domestic

production in the initial situation with no imports. |

|

QSR,Imports |

Domestic

production in the short run, after imports start coming in. |

|

Imports, SR |

Imports in

the short run when the number of firms is fixed at 100. |

|

Point A |

Initial

equilibrium with no imports |

|

Point B |

Short-run

equilibrium after imports start with the number of firms fixed at 100 |

|

Point C |

Long-run

equilibrium domestic production with imports.

All 100 firms exit. There is

zero domestic production. Domestic

demand equals 300 and this is met through imports. |

Now

suppose we have a new situation where imports from China begin to flow into the

U.S. Suppose the good can now be

imported from China at a price of $2.

This drives the price in the U.S. down to $2. In the short run, there remain 100 domestic

firms in the industry. At the lower

price, the domestic firms will contract output.

At the new price equal to $2, each firm reduces quantity to qSR,imp = 1 (where

marginal cost equals the new price). As

the firms cut output, they will cut variable inputs like labor. There are 100 domestic firms in the industry,

so total domestic supply in the short run equals QSR,Imports = 100×1 = 100. (This is point B on the short-run supply curve

with 100 firms.) At a price of P = $2,

demand in the U.S. equals 300 units. The

difference between the demand of 300 and the domestic supply of 100 is made up

by imports of 200 (labeled Imports, SR in the figure).

At

a price of $2, domestic firms lose money.

Each firm’s profit equals (P − ATC)×q or

(2 – 5) ×1 = –3. This loss is illustrated

by the purple rectangle on the left-hand side figure above. On account of this loss, in the long run, all domestic firms will exit the

industry and domestic production will be zero.

The entire demand of 300 units will be met through imports from China. Domestic production (now zero) corresponds to

point C in the graph.

This

is an extreme example, with imports causing the entire industry within the

United States to disappear. Now let’s discuss actual industries.

Part 2. Some Facts: Who is Surviving and Who is not?

In

work with John Stevens at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve Bank

(Holmes and Stevens (2014)), I have looked at industries that have been hit

particularly hard by imports from China.

The paper focuses on 17 industries as having been particularly impacted

by a surge of imports from China over the period 1997-2007. These industries are listed in the table

below taken from the paper.

Table 1: 17

Manufacturing Industries Hit by a Surge of Imports from China between 1997-2007

|

|

Import Share of Shipments (percent) |

China Share of Imports (percent) |

Percent

Change in U.S Employment 1997-2007 |

||

|

Industry |

1997 |

2007 |

1997 |

2007 |

|

|

Curtain &

drapery mills |

8 |

56 |

38 |

65 |

-47 |

|

Other

household textile prod mill |

22 |

68 |

25 |

49 |

-51 |

|

Women's &

girls' cut & sew dress |

29 |

67 |

21 |

55 |

-71 |

|

Women's &

girls' cut & sew suit, |

48 |

92 |

19 |

49 |

-91 |

|

Infants' cut

& sew apparel mfg |

60 |

99 |

08 |

62 |

-97 |

|

Hat, cap,

& millinery mfg |

44 |

80 |

26 |

67 |

-74 |

|

Glove &

mitten mfg |

58 |

88 |

50 |

63 |

-78 |

|

Men's &

boys' neckwear mfg |

25 |

56 |

02 |

59 |

-67 |

|

Other apparel

accessories |

39 |

80 |

35 |

64 |

-75 |

|

Blankbook, looseleaf

binder, |

18 |

47 |

43 |

52 |

-51 |

|

Power-driven handtool mfg |

28 |

56 |

18 |

46 |

-56 |

|

Electronic

computer mfg |

12 |

49 |

0 |

56 |

-68 |

|

Electric

housewares & fan mfg |

52 |

78 |

48 |

76 |

-54 |

|

Wood

household furniture mfg |

29 |

62 |

18 |

46 |

-51 |

|

Metal

household furniture mfg |

29 |

55 |

37 |

85 |

-48 |

|

Silverware

& plated ware mfg |

44 |

91 |

31 |

73 |

-82 |

|

Costume

jewelry & novelty mfg |

31 |

68 |

31 |

67 |

-63 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mean of China

Surge Industries (N=17) |

34 |

70 |

26 |

61 |

-66 |

The

import share of shipments equals the value of all imports (from any country) as

a share of imports plus domestically-produced shipments. For all the industries listed above, the

import share has increased at least 25 percentage points over the ten year period,

1997-2007. On average the import share

increased from 31 to 68 percent. The

table also lists the share of imports originating in China. For all the industries listed above, this

share exceeds 40 percent as of 2007. On average for these industries, the China

share increased from 31 to 67 percent.

This is a remarkably large increase in only a ten-year period.

The

last column of the table reports the decline in U.S. employment for these

industries over the ten-year period. The

declines are dramatic, averaging 66 percent.

Notice in particular what is happening in clothing industries. In the “infants’ apparel” industry,

employment declined 97 percent! The

apparel industry was particularly hurt because of a phase out of import quotas

that took place over this period as part of a world-wide trade

deal between developed countries like the U.S. and Europe and

developing countries. But the effects go

beyond the clothing industry. Look at

computers. In 1997, China accounted for

0 percent of computer imports. In only

10 years, China’s computer industry expanded to the point where it accounted

for 56 percent of imports.

So

what is left? For some industries, like

infants’ apparel, essentially nothing at all.

The industry has virtually shut down like what happens in the long run

in the example from Part 1. For other

industries, such as wood furniture, a sizeable part of the industry

remains. But the part of the industry

that has tended to survive is very different from the part that has left, as I

now explain.

In

1997 and earlier, the wood furniture industry was dominated in the United

States by places like Highpoint, North Carolina with huge furniture factories

with more than a thousand employees. The

factories tended to make standardized products aimed at the mass market. Industry migrated to factory towns like this

in the South many decades ago to take advantage of the low wages in the South

(compared to higher wage locations in the North like in New York and

Minnesota). The craft and

custom-oriented segment of the industry remained in various places throughout

the country. Craft production concentrated

in areas with a large local supply of skilled craftsman (such as Amish furniture

makers). Also, for custom work, it is

often helpful for the buyer to meet face to face with the producer. Few people want to go all the way to North

Carolina to meet the person making their furniture. So firms focusing on custom work tend to be widely

distributed throughout the country and focus on local markets.

Similarly,

as of 1997, much of the U.S. clothing industry was in large plants in southern

locations such as North Carolina, having migrated earlier from higher cost

locations such as New York. New York had

retained some of its garment industry, but it tended to hold onto the fashion

segment of the industry. For the fashion

segment, the benefits of a New York location offset the higher costs. Plants making fashion goods tend to be in small

plants producing output in small batches rather than mass production.

The

impact of China has been most severe in places like Highpoint, North Carolina

with large plants, with relatively unskilled labor. For example, while the wood

furniture employment fell 51 percent overall, in Highpoint it fell 72

percent. Plants doing custom work have

been hurt relatively less. The products

coming out of Chinese factories tend to be close substitutes to the products

coming out of the large North Carolina factories, and poor substitutes for

custom furniture made in Amish craft shops.

Similarly, in the clothing industry, products made in large factories in

China are close substitutes to products made in large factories in the South

and are very different from fashion goods made in New York. This explains why the garment industry has

fallen more in the South than in New York over the past ten years and why small

plants have increased their share of what is left of the industry.

In

summary, those segments of the industry that are surviving here are those for

which China’s comparative advantage is weakest relative to the U.S. These are the custom segments (which works

best when buyers and sellers are near each other) and niche, high-quality,

fashion-oriented segments, which rely on the high skill and creative energy to

be found in places like New York and Los Angeles. While these segments have fared the best, the

long-run prospects for U.S. production in these industries is not good. First, the custom and high-end niche segments

typically represent only a small part of an overall industry. (That is what makes them niche.) Second, advances in communication are

increasingly making it possible for custom projects to be worked out in

long-distance situations, diminishing the comparative advantage of domestic

producers in this segment. Third, China

is moving up the quality ladder, using the experience of massive production

levels at low rungs on the ladder to gain knowledge for climbing to next rungs

on the ladder.

References

Holmes, Thomas J. and John J. Stevens, "An Alternative Theory of the Plant Size

Distribution, with Geography and Intra- and International Trade,” with John

Stevens, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 122, No. 2 (April 2014), pp.

369-421 Link

to prepublication version.

Lett, Erin and Judith Banister, “China’s

manufacturing employment and compensation costs: 2002–06,” Monthly Labor Review, April 2009, pp 30-38. Link

See also

Does

American Need Manufacturing,

Holmes, Thomas J. "The

Case of the The Case of the

Disappearing Large-Employer Manufacturing Plants: Not Much of a Mystery After

All," Economic Policy Papers, Federal Reserve Bank of

"With These Hands,"

Youtube trailer of 2009 film by Matt Barr. The film

is about the last day of work at the Hooker Furniture Factory, a plant near